Image source: Mehakfoodaholics (2019)

“If it were possible to define generally the mission of education, it could be said that its fundamental purpose is to ensure that all students benefit from learning in ways that allow them to participate fully in public, community, [Creative] and economic life.” — New London Group, 2000.

Participatory Culture Discussion

Empowering Youth: The Transformative Potential of Participatory Culture

in Civic Engagement.

There is no simple dictionary definition of “participatory culture.” According to Oxford Reference , it is “Activities which transform the experience of media consumption into the production of new texts, blurring the boundary between producers and consumers.” That was not helpful to me. Wikipedia gave me, in more straightforward “layman’s terms, “…an opposing concept to consumer culture, which is a culture in which private individuals do not act as consumers only but also as contributors or producers.

The term is most often applied to the production or creation of some type of published media.” Still, it was not a thorough enough explanation for me. Through more research, I found Henry Jenkins’ TED talk video about participatory culture incredibly informative and hilarious at times, which made it enjoyable to watch. I desire to help my high school students understand the implications of participatory culture and civic engagement, hence my additional research. His logic is sound, and I am sure I will be able to use it with my future high school students.

Henry Jenkins’ TED talk delves into participatory culture and its implications for civic engagement in the modern world, which I was looking for. He defines participatory culture as one where individuals actively contribute to and engage with media and technology rather than passively consuming it. This concept is exemplified by the increasing number of American teens producing and sharing media content, showcasing a shift in communication patterns and social engagement. Jenkins highlights the historical roots of participatory culture, tracing it back to various forms of community engagement, such as amateur printing presses in the 1850s, amateur radio operators in the 1920s, and the underground press of the 1960s, which illustrate how communities have consistently used new technologies as tools for participation and activism. He argues that participatory culture is a rich site for informal learning, offering low barriers to engagement, informal mentorship, and a sense of belonging and contribution. This notion is exemplified by the emergence of online communities like World of Warcraft, where players collaborate, develop leadership skills, and engage in global conversations. My students will understand this example—many play such video games.

Taking it a few steps further, Jenkins explores how popular culture intersects with civic and political activism, citing examples such as the Harry Potter Alliance, which mobilizes young people around human rights issues, and online movements like AANG Ain’t White, which challenge racial inequalities in media representation. His emphasis on the disconnect between the participatory culture embraced by our youth and the restrictive practices of educational institutions urges us to reevaluate our classroom practices to better align with the skills and interests that today’s young people engage with.

Overall, this TED Talk video underscores the transformative potential of participatory culture in fostering civic engagement, painting a hopeful picture of a more inclusive approach to education. It calls for recognition and leveraging of the skills and knowledge acquired through active participation in media and technology, hinting at a brighter future where our educational practices align with the interests and skills of today’s young people.

Works Cited

TEDxNYED. (2010, March 6). Participatory Culture / Henry Jenkins. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFCLKa0XRlw

In recent years, social platforms have emerged as pedagogical partners to instructors in education relating to language production. As an English teacher hoping to better engage teenagers in the mandatory core standards in the subject, I am specifically interested in TikTok’s relationship to language production in the classroom and how it can be used as a learning tool. There has been a significant change in how many of my students function in the classroom since the onset of the pandemic, and it seems to be heavily related to how involved they have become in online experiences, including online learning, since that time.

As I explored the subject for this paper, I found few published results of empirical studies related explicitly to TikTok and language production, most of which were comprised of small sample sizes that cannot be overgeneralized. However, much discussion about it in the general social media population made me believe it may be worth experimenting with in my classroom.

YouTube and other social media sites regularly present educational courses and online lessons for classroom use (Brame). TikTok is different in the way they have taken the idea of educational videos that are more traditional in length and generated “micro-learning” videos

that are quick 15-second bursts of learning geared towards culture and vocabulary (Zemach). Microlearning is not new, but since TikTok’s inception, the idea of it has gained momentum because studies have shown that microlearning can enhance a student’s ability to retain information (Giurgiu). A study by Hashim (2022) concluded that “TikTok is indeed an effective teaching tool, especially when it comes to teaching regular verbs and sentence construction,” and TikTok has taken advantage of students’ ubiquitous use of hand-held technology to expand microlearning as a learning tool since it has become the primary way students obtain information. Zemach (2021) discussed that microlearning may specifically be a better way to reach students in classrooms today because of their difficulty paying attention to long lectures or traditional lesson plans.

This issue calls for more “shortened bursts” of learning that better meet their attention span capabilities. Jacobs and Pan (2022) suggest that recent studies indicate attention span and recall ability decrease with long, uninterrupted, teacher-directed learning sessions where “…the greatest impact of learning appeared within the first five minutes with a declining impact thereafter.” The traditional style of the teacher talking and the student listening has become relatively ineffective in recent decades as students have become ardent users of short online video clips and interactions. TikTok content creators are not just working with English teachers to produce engaging, sometimes humorous, micro-bursts of learning that students can repeatedly refer to as they study for quizzes or tests; many are English teachers themselves.

Fanbytes by Brainlabs, an award-winning influencer marketing platform, wants to focus on making education more enjoyable: “Combine informative, short videos with engaging and enjoyable content, and a new form of learning format is born. Welcome to ‘edutainment’ TikTok.” With educators like me striving for ways to bridge the academic learning gaps students have demonstrated since returning to the classroom, TikTok’s type of microlearning may be one means of achieving that goal. During the pandemic, TikTok launched a $50 million Creative Learning Fund as part of a $250 million initiative to support communities. It specifically assists creators in producing educational content, provides resources for learners, and introduces emerging teachers to the platform.

Bill Nye, Tyra Banks, and Neil deGrasse Tyson are just a few of the famous names that have been engaged in the effort. TikTok emphasizes that the joy of learning on its platform lies in the creative format of instructional content, which teaches valuable skills and inspires users to explore further information enjoyably and engagingly. The community has been particularly drawn to videos showcasing English Language Arts, unique science experiments, practical life hacks, creative math tricks, easy DIY projects, and motivational messages and advice. Their launch helped me decide to learn to participate in using the platform in the classroom as well. Therefore, how can TikTok expressly meet my goal of language learning in English Language Arts?

Because TikTok videos are typically short, they are ideal for small, digestible chunks of content. Many TikTok users create content related to literature, poetry, and creative writing, and I have found short ELA skits for grammar and varied literature genres, educational snippets, and literary techniques. Engaging students with these types of videos inspires them to write their own compositions. My students thoroughly enjoyed creating TikTok videos for their mini-literature analyses and flash-fiction videos for their poetry, and TikTok’s algorithms made creating these new lesson plans easier, as they learned my preferences based on the content I interact with, providing a personalized feed for me on the For You Page (FYP).

I have been learning to train the algorithm to recommend more relevant videos to support my language learning journey for students, mainly because TikTok often features challenges and trends that prompt users to create content around specific themes or topics. Usually, ones they may not think of themselves.

Another exciting factor about TikTok is that it hosts a diverse range of creators from various English-speaking regions. Watching videos from native speakers exposes my students to different accents, slang, and colloquial expressions, which helps improve their listening comprehension and overall understanding of the language.

In conclusion, TikTok can be a surprisingly effective tool for language arts learning, even though it is not in a traditional sense. Integrating it into a classroom routine can add an enjoyable and interactive dimension to high school English Language Arts studies. While it does not replace required resources like textbooks and necessary literature reading, it can supplement my day-to-day practices for a well-rounded learning experience.

Works Cited

Brame, Cynthia J. Effective educational videos. 2015. <https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/effective-educational-videos/>.

Hashim, Shevany Anumanthan and Harwati. “Improving the Learning of Regular Verbs through TikTok among Primary School ESL Pupils.” Creative Education 13.3 (2022): 896-912.

Jacobs, Aimee & Pan, Yu-Chun & Ho, Yen-Chen. “More than just engaging? TikTok as an effective learning tool.” The 27th UK Academy for Information Systems International Conference . Research Gate, 2022.

Literat, Ioana. “Teachers Act Like We’re Robots”: TikTok as a Window Into Youth Experiences of Online Learning During COVID-19.” AERA Open 7.1 (2021): 1-15.

TikTok & Education: How TikTok Is Transforming Education For Gen Z. 2022. <https://fanbytes.co.uk/tiktok-and-education/>.

TikTok Announces #LearnOnTikTok Initiative to Encourage Education During Lockdowns. 28 May 2020. June 2022. <https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/tiktok-announces-learnontiktok-initiative-to-encourage-education-during-lo/578805/>.

Zemach, Dorothy. Teaching English With TikTok? How Social Media Is Making Microlearning Big Business. 20 May 2021. 20 June 2022. <https://bridge.edu/tefl/blog/teaching-english-with-tiktok-social-media-making-microlearning-big-business/>.

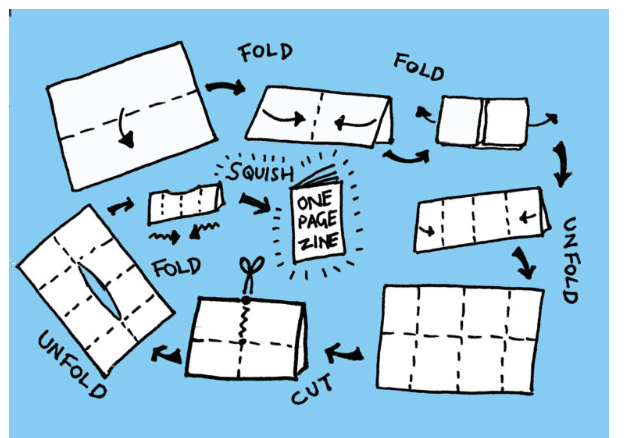

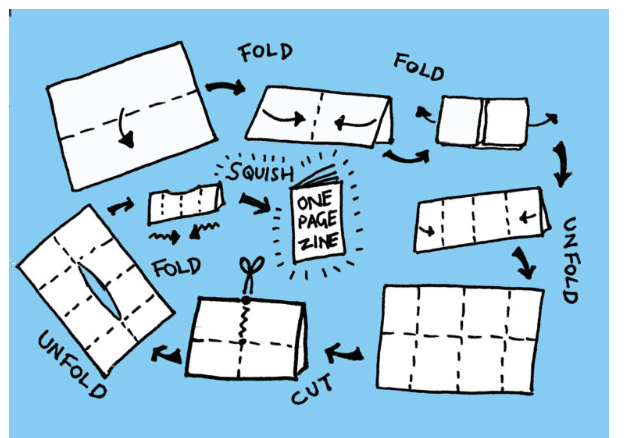

Beyond the Five Paragraph Essay: Zine-Making for College Writers

Contemporary college educators actively seek to move beyond the confines of composition writing courses that adhere to the restrictive and formulaic structure of the five-paragraph essay. They aim to liberate students and encourage them to “explore, explain, and express” their ideas freely (Bomer, 2016, p. 22). The traditional five-paragraph essay format is criticized for its limitations because it often confines students’ thoughts to superficial engagement, which fails to teach them valuable life skills and often results in weakly developed papers. To depart from these conventional text-based writing practices, educators are turning to visual and multimodal composition techniques that enable students to delve into various communication methods and foster habits of mind such as curiosity, open-mindedness, active engagement, creativity, adaptability, and metacognition. Zine-making is one means of transcending text-based writing courses.

Zines, also referred to as “fanzines,” are small-circulation periodicals produced and distributed independently. They serve as an agency for personal expression, primarily focusing on facilitating communication and fostering communities, particularly within marginalized demographics. Zine pedagogy challenges traditional approaches to academic writing in college courses by providing students with a platform for critical engagement with societal issues, therefore empowering them as drivers of societal change. This pedagogical approach within first-year college composition courses is structured around three key areas of framework: exploration, meaning-making, and critiquing (Brown et al., 2021). In the exploration phase, students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning experiences and identify the aspects they find most significant, which they aim to capture and express in their maker-space arena.

Meaning-making encourages students to consider the most effective ways to convey their thoughts, emotions, and messages, whether through text, visuals, or a combination of both.

Furthermore, incorporating multimodalities helps underscore a topic’s relevance and its broader social implications. This prompts students to question the societal impact of their messages. Finally, critiquing plays a pivotal role in this framework, empowering students with the tools for critical analysis and self-reflection as they engage in the creative process.

Rallin and Bernard (2008) maintain that studying and creating zines aligns with current trends in composition studies that emphasize community engagement. They quote scholars like Thomas Deans and Paula Mathieu, who encourage students to write within nonacademic discourse communities by urging educators to move beyond standardization and instead embrace discursive projects in various community contexts. The focus is extending the writing experience beyond the traditional university composition constructs. This shift in composition studies encourages the connection of student writing to real-world texts, events, and issues. Lonsdale (2015) emphasizes the use of zine-making for underrepresented and marginalized groups: “Zines provide an opportunity for those who feel invisible—those who exist on the margins—to speak out about their lives and interests…[and] are an inviting format for communication, an alternative to the traditionally valued forms of media and expression where they do not see themselves represented.” They are a form of personal expression that encourages classroom community engagement.

The student assignment, “Zine-Making for College Writers,” is an integral part of a university-level first-year composition course. It is placed within the larger context of the writing course, “Visual and Multimodal Composition,” in which students explore various communication methods and expressive forms that shape our world and go beyond conventional text-based writing. Crafting zines is only one topic the course will cover, as it will also include analyzing visual rhetoric and intentionally employing rhetorical strategies using language, imagery, and design to convey distinctive messages and engage an audience in several multimodal ways, including digital storytelling, infographics, and even podcast production.

Gagich (2020) describes all writing as multimodal since “any combination of modes makes a multimodal text,” (p. 42), and zines fit this description as part of a broader course. She distinguishes the five modes of communication that will be included in the overall course: linguistic—written text or the spoken word with an emphasis on how words are used; visual—what the readers can see; spatial—how the text and visuals are dealt with in the space including organization and emphasis; gestural—texts and visuals that “capture” movement and gestures; and aural—such as podcasts and other representation of sound or the absence of it. The course provides an overview of multimodal composition and includes various communication modes to enhance students’ writing skills and creative expression.

Throughout the four-week assignment students will study the history of zines, read, analyze, and write about them, and then work collaboratively to make their own while offering guidance, reflection, and direction to others. They will explore how zines use rhetorical techniques to address issues related to their specific audience and promote diversity within that audience. Classroom community engagement in this project is essential as it confronts rigid, established academic writing structures and instead fosters new forms of expression and community building among students.

Twenty-first-century college composition skills need to focus on the power of writing through language, drafting, editing, publishing, and collaboration, emphasizing the importance of identifying rhetorical contexts for audiences and purpose; and a convergence of various writing strategies that are appropriate for academic writing that actively engages the texts of others. It is not about putting an end to formal college composition skills such as writing thesis statements, proper paragraph development and organization, and other major composition elements taught in high school and refined at university. It is about equipping students with a broader range of composition skills that are highly relevant in a digital, interconnected world that prepares students for success in academic and professional contexts.

Higher education composition writing should reflect the evolving landscape of communication and technology while also addressing the core principles of effective writing and critical thinking skills to construct well-reasoned arguments. It must consider cultural competency as students navigate issues of diversity and identity within their writing. Students should engage in reflective practices that evaluate and revise their own writing processes. Group work must be integrated into the course as well, including peer editing and collaborative multimodal projects. Most importantly, college composition courses should include writing assignments that connect to real-world contexts and contemporary issues that reflect our digital age and focus on developing a versatile set of skills for effective communication. Adaptability to a rapidly changing world will be essential to the future of university students.

Works Cited

Bomer, K. (2016). The Journey is Everything: Teaching Essays that Students Want to Write for

People who Want to Read Them. Heinemann.

Brown, A., Hurley, M., Perry, S., & Roche, J. (2021). Zines as Reflective Evaluation Within

Interdisciplinary Learning Programmes. Frontiers in Education,6(6).

https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.675329

Gagich, M. (2020). An Introduction to and Strategies for Multimodal Composing. Writing

Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 3 – The WAC Clearinghouse.

https://wac.colostate.edu/books/writingspaces/writingspaces3/

Lonsdale, C. (2015). Engaging the “Othered”: Using Zines to Support Student Identities.

Language Arts Journal of Michigan, 30(2), 8-16.

https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.2066

Rallin, A., & Bernard, I. (2008). The Politics of Persuasion versus the Construction of

Alternative Communities: Zines in the Writing Classroom. Reflections (7)3, 46-57.